Recording Clare’s Holocaust memories was often harrowing. This was not surprising, given the nature of the memories and my concern that I would rake up further trauma in recovering them. The code for oral historians puts the wellbeing of the person interviewed ahead of all other considerations, but the biography I was to write demanded teasing out difficult areas and looking at things differently. How far should I dig to get at the so-called ‘truth’? Fortunately Clare proved strong enough to allow me to dig deep.

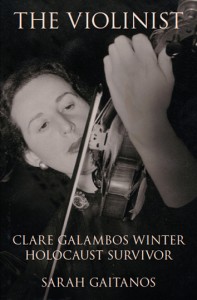

The Violinist: Clare Galambos Winter, Holocaust Survivor

This article is based on a presentation I gave at the International Oral History Association (IOHA) conference in Prague in July 2010. The conference started with master classes which I found extremely poignant given the topics discussed, all the more so because it was 7 July, the anniversary of the day in 1944 when my Hungarian-born narrator, Clare Galambos Winter, then known as Klári, arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. It was the last time she saw her mother and 14-year-old brother who were presumably sent to the gas chamber soon after their arrival. Together, 20-year-old Klári and her 35-year-old aunt Rozsi survived.

This article is based on a presentation I gave at the International Oral History Association (IOHA) conference in Prague in July 2010. The conference started with master classes which I found extremely poignant given the topics discussed, all the more so because it was 7 July, the anniversary of the day in 1944 when my Hungarian-born narrator, Clare Galambos Winter, then known as Klári, arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau. It was the last time she saw her mother and 14-year-old brother who were presumably sent to the gas chamber soon after their arrival. Together, 20-year-old Klári and her 35-year-old aunt Rozsi survived.

Like many Holocaust survivors, Klári tried for years to put the past behind her. She wanted to forget. She and Rozsi returned to Hungary after the war in hope of finding survivors in the family, but it held too many memories and they hated living among the people who had betrayed them. In 1949 they emigrated to New Zealand, as far from Europe as possible, where they could make a new life without being constantly reminded of the old. Klári changed her name to Clare. Now 87 years old, she often says she was ‘born in NZ’.

Clare joined the fledgling National Symphony Orchestra which became her family for the next 32 years. She rarely talked about her past until her retirement in 1983 when second husband, Otto Winter, a Jew from Czechoslovakia, encouraged her to record her memories of the Holocaust. I referred to these earlier accounts when I started my own oral history interviews with Clare in 2005.

Despite decades of silence, Clare has vivid recall of some events of the Holocaust, but time has changed and eliminated others. This loss is to some extent compensated by the mass of material that is now available in way of other people’s memoirs and primary documents, and recent scholarship other researchers have brought to the subject. Thanks to the Internet, it was possible to fill some of the gaps in ways I couldn’t have done so earlier from New Zealand. It was nevertheless necessary to carry out in-the-field research in Hungary, Poland and Germany. My timing was fortunate: in 2008, ITS, the Red Cross International Tracing Agency (ITS) in Bad Arolsen, Germany, released 50 million files.

How were Clare’s versions of the Holocaust affected by my wider research? This is the question I am often asked, and the subject of my paper in Prague in which I gave the following examples.

Klári was a violin student in Budapest when, on 19 March 1944, the German army occupied Hungary. Until then the Hungarian Jews had suffered but not feared for their lives in the way that Jews in the rest of Europe had done. Everything now changed for them. Terrified at the sight of German tanks rolling through the city, Klári wanted to flee Budapest and go home to her family in Szombathely, a provincial town in the west of Hungary near the Austrian border. She describes how ‘three days’ after the invasion she went to the railway station with her non-Jewish boyfriend, Sandor: (Listen to the way she reconstructs her story.)

Sándor my boyfriend came and we had no money, we couldn’t take things like taxis, we went by bus or by – I think it was by bus – it must have been. It wasn’t trams, because there were trams also in Budapest but no, I think it was by bus – but we couldn’t sit next to each other because I had the yellow star. The yellow stars all had to go to the back and sit squashed up with all the other non-human people wearing the yellow star. And then, again I can’t remember how we got together again at the railway station but all I remember is that Sándor said, “I am going to take your big luggage and put it in the luggage van.” … So he has done that, he has put it up, and as we walked into the railway station there was a man there who looked at us and said, “Jews that way, non-Jews that way,” so we were immediately separated, and that’s when Sándor said, “I’ll put this onto the train”, and I remember getting on my tippy-toe and looking for him, and said “See you later”. “Yes, don’t worry”. I never saw him again.

After we have been over 20 or 30 people we were gathered together, we were all standing around there, and the man pointed at the door that we should go in there and so we all went over to the door and the door was opened, and it wasn’t an office, it was an outside door, and we were herded across the street, and there was a jail. It was a holding jail – it wasn’t a proper-proper jail – it was only for people who they had picked up on the street, whores and such like, until they could be processed to go into a proper jail.[1]

Clare has strong recollections of the next fearful days in this overcrowded jail, her first experience of being treated like an animal, and her bewilderment that this should happen to her in Budapest, the beautiful city of her birth. She recalled that on the ‘third day’ (three days is a way of saying it was more than a day and less than a week) the doors were opened and without explanation of why they had been held or why they were being freed, they were told to scram.

While the main interest is her account of these days, my problem as a biographer was fitting the event into the chronological sequence of events. Klári said this happened in the days immediately after the occupation, and that she was wearing the yellow star. But the decree that declared all Jews had to wear a yellow star didn’t come into force until 5 April. Did this event occur after that date? Could ‘three days’ have really been 15 days or more? Possibly. But on further discussion, it became apparent that Clare assumed she wore the yellow star. She had reconstructed what she thought must have happened, not what she remembered. (She probably also misplaced a later memory.) When I discussed this with her she said she must have been wearing the yellow star – how else would they have known who were the Jews when she arrived at the railway station? But as she explained in an earlier account, Jews had to carry identification papers, and they would simply have obeyed the order.

Establishing that this event had occurred as she said, in the first days after the German occupation, puts it in a context that not only gives a better understanding of what happened to her, it also adds to the record of that course of historical events through her personal testimony. This is the context:

In the days immediately following the occupation, thousands of Jews were detained in and around railway stations in Budapest on the pretext of disobeying a new law – not yet announced – that required them to obtain written permission to travel. They were released some days after a meeting that took place on 28 March between Hungary’s Jewish leaders and Nazi SS officers when the Jewish leaders requested the three thousand or more Jews who had been arrested be returned to their families. The real reasons for the arrests were several: to get rid of opposition; to make a show of German control; to create an atmosphere of fear and chaos; and to provide hostages for negotiating with the Jewish leaders.[2]

Klári didn’t know any of this.

She did eventually get home to her family. In the second week of May, the Jews of Szombathely were evicted from their homes and ghettoised.

On 4 July the Jews of Szombathely were deported, arriving on 7 July at Auschwitz–Birkenau. Today the memorial site looks very different, but its scale and purpose is nonetheless undeniable and overwhelming.

The Jews of Szombathely were among the last to arrive from provincial Hungary. The world now knew about Auschwitz and under pressure from other leaders, Hungary’s head of state, Miklós Horthy, had stopped deportations on 6 July, foiling Eichmann’s plans for the Jews of Budapest.

By this time, new arrivals at Auschwitz-Birkenau were no longer being registered and selection processes were increasingly chaotic, but a selection obviously took place and Clare recalls the SS officer at a flick of his finger, directing her and her aunt in one direction, her mother and brother in another. Those selected to go into the camp were showered, shaved all over, given rags to wear – and by this time they really were rags. Clare says she regarded all this with utter disinterest. The only thing she thought about was her thirst and hunger. She had no idea where in the world she was – she had never heard of Auschwitz and knew little about Poland. She wondered where her mother and brother were and when she would see them. Other survivors recall the smell of burning flesh, but Clare has no memory of this. There was talk of burning Jews. Others recall their fear of the gas chamber. Clare says the idea was beyond belief. What a person once knew or didn’t know is as questionable as memory itself, but I don’t doubt her disbelief.

Clare said that she and Rozsi were in C-Lager, and I didn’t at first question that – the Hungarian women were in C-Lager. I narrowed my focus. But I was aware of discrepancies, and when I talked to her after going there myself, these became more worrying. Conditions in C-Lager were worse than in other camps in Section BII – they didn’t have bunks, for example, but they did have kitchen barracks and ablutions blocks, and rudimentary plumbing.

Clare was adamant that in her camp the reconstructed barrack with its latrines were uncovered, that her camp had no kitchen facilities and their food, such as it was, was brought in from outer camps. And Clare recalled she could see the gypsies from her camp – they were diagonally opposite. Not if she had been in C-Lager. Her accounts made better sense when I eventually did consider the possibility that she was somewhere else.

But when I myself was at Birkenau I thought, what do these things matter? They seemed inconsequential in the face of what happened at there, where the Nazis systematically, in cold blood, murdered one and a half million people, mainly Jews. Klári’s account of what it was like to be in Birkenau rang true, wherever she was.

When I eventually did consider the possibility that she and Rozsi were not in C-Lager, I discovered they were probably among the 30,000 unregistered Hungarian women, the last to arrive, who were concentrated in Section BIII, a so-called ‘transit camp’ nicknamed ‘Mexico’ by inmates of other camps, because it was for the poorest of the poor, and because the rags they were – not clothing – looked like ponchos. The camp was still under construction, it had no plumbing, no ablution blocks or kitchen facilities, but the rest of the camp was full and there was nowhere else to put these last arrivals. Clare had never heard of a camp called ‘Mexico’ but it affirmed some of her other memories.

How long she and Rozsi were in Auschwitz-Birkenau was always open to question. One can understand that time seemed to stand still. Their Nazi files show they were registered in Auschwitz on 13 August, before being transported with 1,000 Hungarian women selected to work in an ammunitions factory at Allendorf (now Stadtallendorf) in central Germany. They arrived there on 19 August.

In Allendorf, conditions were quite different, better, and they had something to do, even though it was heavy dangerous work handling poisonous materials to make bombs. The camp where they lived was about half an hour’s brisk march from the factory. Klári describes the first time they went to the factory, through dense pine forest for a long time until they came to an opening in the mountain:

It was just like a cave. And we found ourselves walking more and more in obviously a dugout walkway and we came out the other end and we looked around and there were huge buildings and on the top of the buildings, three, four, five-storey buildings, there were trees growing on the top of the buildings, so from the aeroplane you couldn’t see a thing, because it was just one level of pine trees. It was very difficult for me to say anything nice about the Germans but that a brilliant piece of engineering.[3]

Clare regarded photographs of these now whitewashed buildings with disbelief. There is no mountain, but there were tunnels, and while she had probably exaggerated the heights of the buildings in her memory, they would have looked higher as she came upon them suddenly out of the tunnels, close up in the dark under the overhanging canopy. Of course in this case she had no sense of orientation and no idea of the whole complex. Her memory is valid because even though magnified, it gives us an idea of how different it looked from the prisoners’ perspective.

On the other hand, photos of exhibits such the bombs she had filled were very familiar. Klári describes in detail how to make grenades and bombs. The dynamite, she says, came in boxes with a metal strap that stuck out, which she remembered because they slept on those boxes in the boiler room where she mostly worked, filling the vats.

With so many bad memories, it was a relief when Clare had a good memory. She remembers their supervisor, a great big man with a great big voice called Peter Peters, a German Democrat from Danzig. In the Gieshaus, in the time between filling the vat and refilling it, when the bombs and grenades were being filled on the floor below, he allowed the women to lie down and sleep. When the SS returned, Peter Peters warned them. Clare says, ‘We woke up to Peter’s huge booming voice yelling at us, calling us “filthy Jews and lazy whores”. We loved him for it because he spoke the Nazi language to us, but we knew he didn’t mean it.’[4] The same scheme worked for air raids when the SS left to shelter in bunkers.

Other survivors have told this story, according to staff at the Documentation and Information Centre in Stadtallendorf. They knew him only as Peter. It was gratifying to record the kindness of Peter Peters, and to know where he came from and give him his full name.

Nothing conveys these events more powerfully than eye witness accounts, but all records – documentary and personal accounts – throw light on each other. Even then, there is often room for doubt. I have to acknowledge that we who weren’t there can imagine, but never really know, what it was like for those who were.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Primary sources:

Clare Galambos Winter, interviewed by Sarah Gaitanos, Wellington, 2005-2006.

Clare Galambos Winter, interviewed by Joy Tonks for the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, 1999.

Clare Galambos Winter interviewed by Jason Walker, ‘Survivors of the SHOAH’, recorded on video by the Visual History Foundation, 13 December 1997.

Clare Galambos Winter, unpublished memoir.

Nazi records and personal files held at the Red Cross International Tracing Service (ITS), Bad Arolsen, Hesse, Germany.

Photographs by Sarah Gaitanos; pre-war photos of Klári Galambos and her family.

Secondary sources:

Braham, Randolph L., Published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary, Wayne State University Press, 2000.

Brinkmann-Frisch, Fritz, ‘Allendorf (“Münchmühle”)’, Der Ort des Terrors, Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, Herausgegeben von Wolfgang Benz und Barbara Distel, C.H. Beck, München 2006, Band 3.

Hacker, Iván, Unser Weg Die Hölle, Ungarische Juden in Den Klauen Der SS Ein Authenticher Bericht, 1998

Kaszas, Susan, From Love to Triumph, Letter-diary written 1945,

AIL New Media Publishing, released online 2005, Translator, Steven Kingsley.

Kery, Iby I’ve Been Chosen, Castlecrag, N.S.W. c1985. (DIZ Stadtallendorf).

Porter, Anna, Kasztner’s Train: the true story of an unknown hero of the Holocaust, Scribe Publications, Melbourne 2008.

Ranki, Vera, The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion: Jews and nationalism in Hungary, Allen & Unwi, Australia 1999.

Steinbacher, Sybille, Auschwitz, Penguin, London 2005.

Stark, Tamás, Hungarian Jews During the Holocaust and After the Second World War, 1939-1949: a statistical review, translated by Christina Rozsnyai, East European Monographs, Boulder, distributed by Columbia University Press, New York, 2000.

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum: A Brief History and Basic Facts

Publisher: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2005, Ed. Teresa Świebocka, Jarko Mensfelt, Jadwiga Pinderska-Lech.

Documentation-and-Information-Centre, Stadtallendorf, Permanent Exhibition, Editor Fritz Brinkmann-Frisch, translator Lydia Hartelben, 1994.

Emlékezzünk az áldozatokra: A budapesti zsidóság holocaustja 1944, (Let’s Remember the Victims, The Holocaust of Jewry of Budapest, Jewish Agency 1994), Szerzö: Professor Dr Ságvári Ágnes történész. Budapesst, 1 March 1944.[?]

JewishGen Hungary Database, http://www.jewishgen.org/databases/Hungary,

Jews of Szombathely: Registration of 3,116 Jews in Vas County, 1944

Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/

Other key websites:

http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/

http://www.iremember.hu/index2.html

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/images/logoBanner.jpg

http://www.scrapbookpages.dom/auschwitzscrapbook/History/Articles

[1] Interview, Clare Galambos Winter to Sarah Gaitanos, 10 August 2005, side 10.

[2] Braham, Randolph L., The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary, Wayne State University Press, 2000; Porter, Anna, Kasztner’s Train: the true story of an unknown hero of the Holocaust, Scribe Publications, Melbourne 2008; Ranki, Vera, The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion: Jews and nationalism in Hungary, Allen & Unwin, Australia 1999.

[3] Clare Galambos Winter to Sarah Gaitanos, 14 November 2005 side 20.

[4] Clare Galambos Winter to Jason Walker Survivors of the SHOAH, recorded on video, Visual History Foundation, 13 December 1997, tape 5.